This week is going to be about one of the most massive explosions in the Universe: Supernova. Last week, when discussion the star life cycle, I had mentioned supernovae* briefly as an outcome of the death of super massive stars. But that is only one kind of supernova, there happens to be two types which are further subdivided.

*The plural of supernova is supernovae.

|

| The Crab Nebula, the remnant of a supernova recorded by Chinese astronomers in 1054. (Credit: NASA) |

A supernova is an extremely luminous explosion of a star with a burst of radiation that often briefly outshines the entire galaxy in which the star resides. It can take several weeks or months for a supernova to fade, over this time it can emit as much energy as the Sun over its whole life span. The explosion expels most, if not all, of a star's matter into space, creating a shock wave. The shock wave sweeps up dust and gas from the star an the interstellar medium, creating at supernova remnant. These remnants are usually what you see in images from the Hubble Space Telescope and other telescopes.

|

| Supernova 1994D (the bright 'star' on the bottom left) in Galaxy NGC 4526. (Credit: HST/NASA/ESA) |

The word nova means "new" in Latin, referring to what appears to be a bright new star in the night sky. Occasionally these explosions cause what appears to be a new star in the sky. The prefix 'super-' separates a supernova from an ordinary nova, which also involve a star increasing in brightness, though to a lesser extent and through a different mechanism.

Types of Supernova: there are two basic types of supernova, and a couple of other distinctions:

|

| Illustration of different ways a supernova is formed. (Source) |

Type Ia: These result from some binary star systems in which a white dwarf absorbs matter from a companion. (What kind of companion star is best suited to produce Type Ia supernovae is hotly debated.) The idea is that so much mass piles up on the white dwarf that its core reaches a critical density that results in an uncontrolled fusion of carbon and oxygen, thus detonating the star.

Type Ib and Ic: These ones look similar to Type Ia when looking at their spectrum, but are distinguished because they lack certain different lines of spectra. The lack of spectra means that elements in the core may have been lost due to other means, and in general Type Ib/c may be referred to as stripped core-collapse supernovae. These types of supernova are also incredibly rare, and their sources might also be the progenitors of gamma ray bursts.

|

| The onion like layers of a star's core before going supernova. |

Type II: A common supernova type, usually found in the spiral arms of galaxies and not in elliptical galaxies, they are distinguished by the presence of hydrogen in their spectrum. These are known to be caused by the rapid collapse and violent explosion of a massive star. There exists several subcategories of Type II supernova, including II-L, which has a steady, linear decline in light over time; II-P which has a slower decline (a plateau) followed by normal decay; IIn, the "n" denotes narrow, which have narrow hydrogen emission lines in their spectrum (probably caused by blue variable stars); and IIb, which initially resembles a Type II supernova but later has a spectrum resembling Type Ib.

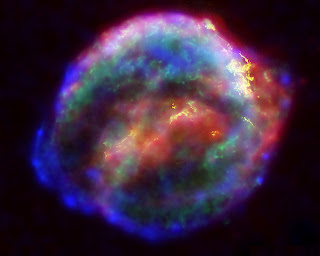

Those are the general types of supernova known to astronomers. After the explosion the cores are left behind and usually create a neutron star or a black hole. Supernova are pretty rare events in a galaxies, the Milky Way experiences one about every 50 years, though the last one seen from Earth was in 1604. This last one was known as Kepler's Star and was easily visible in the night sky, brighter then all the planets except Venus. It was visible during the day for over 3 weeks.

|

| False-color of the remnant of SN 1604 (Kepler's Star). (Credit: HST/NASA/ESA) |

There are several large candidates in the Milky Way that might go supernova in the next million years, these stars include VY Canis Majoris, Betelgeuse, and Eta Carinae. Once these stars explode, they will provide a vital part in stellar evolution. Supernova explosions are the source of many heavy elements including uranium and plutonium. All of these elements get shot out into space and form clouds of dust that eventually condense and form new stars, or the shock wave can trigger star formation in an already present cloud. This is likely the cause of formation for our own star. This includes the Earth and us. We owe our existence to these violent explosions, the death of a star. As Carl Sagan would say, "We're made of star stuff."

Thanks for reading! This was my 100th post on this blog. It hardly seems like it, I only started back in February. I really have enjoyed writing these posts for my readers, and I enjoy the feedback. I hope you have learned some new things about astronomy from what I've written, or at least enjoy the pictures. I think supernovae are a good way to celebrate. Thank again for reading and I plan to continue this for as long as I can.

6:22 PM

6:22 PM

Astronomy Pirate

Astronomy Pirate

Posted in

Posted in

18 comments:

We are all made of star stuff! :D

Congrats on your 100! And yeah, the false-color images are always incredibly stunning.

Insert cheezy joke here: My buds from Oasis want to know about the rare Champagne Supernova. Can you tell us more about that?

Congrats for the 100th post! And I wish that a star go supernova in our lifetime so we can see it in the sky during the day... would be awesome!

You're right. Those were some awesome pictures.

I feel so much smarter when I read your blog!! Congratulations on 100 posts - I hit the mark tomorrow!!

wow, a hundred posts! keep em coming!

I remember learning about how elements were created in supernovae. Being literally made of star stuff. Blew my mind.

Always learn something new here, congratulations on 100.

Interesting reading. I read somewhere, that there is another type of supernova, a giga- or hypernova that explodes with a gigant gamma ray burst and if it would happen in a few lightyears range near us it could still harm us by its massive rays. But fortunately only the most massive stars cause such explosions and we got only two candidates in our galaxy, far away.

100 is a lot - congrats!

Damn this is just amazing tbh ;D

@Idaho, I don't listen to Oasis, so I totally had to Google that to get the joke...

@mindph, hypernovae and collapsars are interesting theoretical objects, I don't know that there is any direct evidence for them though. I think there is a growing consensus that they might be more related to Type Ib supernovas.

Supernovas FTW

Gotta love Nebulas with flashing rementants of the stars in the center

great educational and interesting article. Our Milky Way experiences one every 50 years..Wow, must be many black holes out there, i mean here, lol

I just love the pics. Cheers.

100! I'm glad you are not testing us. If you were, I'd throw start stuff in your face.

"What kind of companion star is best suited to produce Type Ia supernovae is hotly debated."

Is that a pun? (Seriously, I don't know.)

I feel educated.

;) thanks

congrats

Post a Comment

Comments are moderated, please no advertising or profanity. This also helps me see who is dropping by.